Drug shortages aren’t just inconvenient-they’re life-threatening. In 2024, the U.S. saw over 300 active shortages, with hospitals scrambling to find alternatives for antibiotics, chemotherapy drugs, and even basic IV fluids. The federal government has responded with a mix of new programs, funding shifts, and policy changes, but the results are mixed. Some actions are helping. Others are falling short-or even making things worse.

What’s Actually Being Done?

The centerpiece of the federal response is the Strategic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Reserve (a federal stockpile of raw drug components, not finished medicines), or SAPIR. Launched in 2020 and expanded by Executive Order 14178 in August 2025, SAPIR targets 26 essential medicines, including life-saving drugs like epinephrine, insulin, and cancer treatments. Instead of storing finished pills or injections, the government is stockpiling the raw ingredients-APIs-that go into them. Why? Because APIs cost 40-60% less to store, last 3-5 years longer, and are easier to transport than finished drugs. It’s a smarter way to prepare for crises.

The goal is to reduce dependence on foreign suppliers, especially China, which produces about 80% of the APIs used in U.S. medications. The idea is simple: if a factory overseas shuts down, the U.S. can quickly turn its stockpiled ingredients into life-saving drugs. Since August 2025, the Department of Health and Human Services claims SAPIR has already prevented 12 potential shortages of critical antibiotics. But there’s no public data to verify that.

How the FDA Is Trying to Fix Shortages

The FDA (the agency responsible for regulating drug safety and supply) has long been the front line in managing shortages. Its approach is hands-on: it works directly with manufacturers to fix problems before they become full-blown crises. In 85% of cases, the FDA helps resolve shortages by speeding up inspections, allowing temporary imports, or approving alternative production methods.

A real-world example? The 2018-2020 saline shortage. When production at a major plant failed, the FDA worked with seven other manufacturers to ramp up output. Within months, the shortage was gone. That’s the kind of quick, practical action that works. But now, the FDA’s tools are being weakened. The agency’s own internal review, leaked in October 2025, found that only 15-20% of future shortages could be prevented under current policies. Why? Because the focus is too narrow.

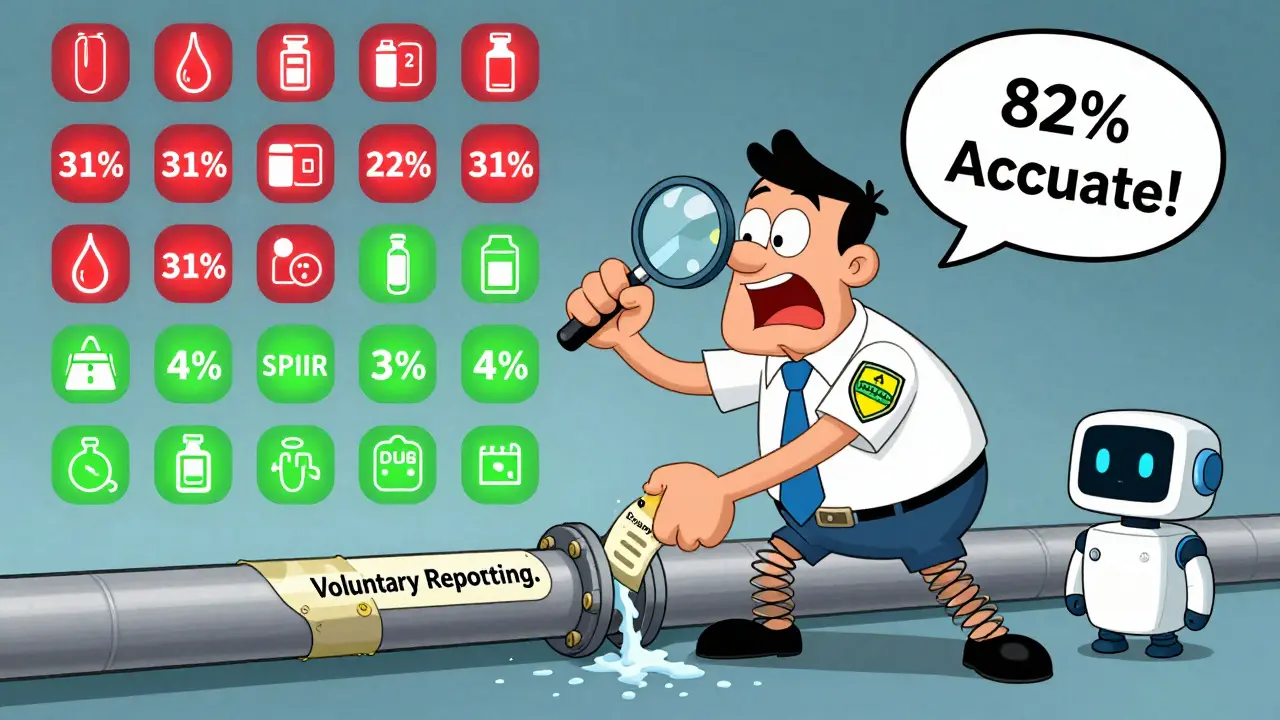

Of the 1,247 drug shortages tracked by the FDA since 2012, only 4% involve the 26 drugs in SAPIR. Yet 31% of all shortages are in oncology drugs-drugs that aren’t even on the reserve list. Meanwhile, compliance with mandatory shortage reporting remains below 60%. Small manufacturers, who make up most of the supply chain, are the least likely to report problems. Without better data, the FDA is flying blind.

The Bigger Problem: Manufacturing Concentration

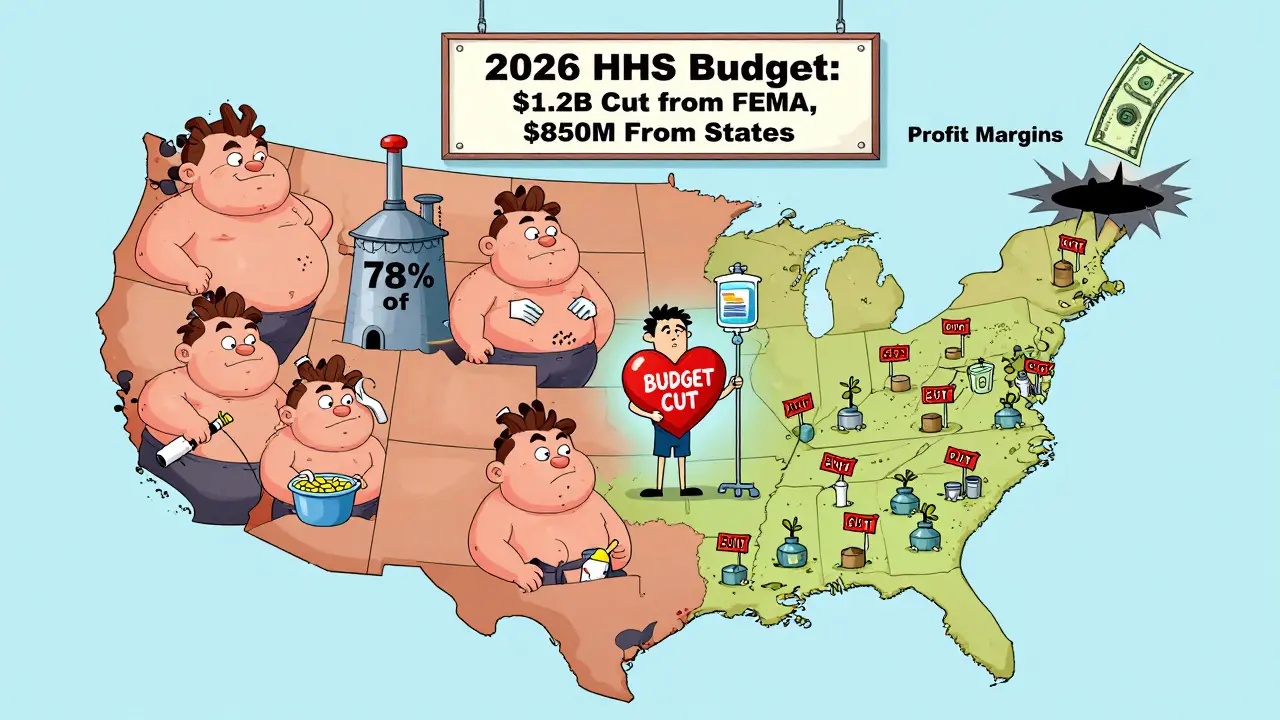

The real issue isn’t just foreign supply-it’s how few U.S. factories make these drugs. Just five facilities produce 78% of all sterile injectables. Three companies control 68% of the market. If one of them has a problem, dozens of drugs vanish overnight.

That’s why experts call the current strategy “reactive.” Stockpiling APIs helps when disaster strikes, but it doesn’t stop the disaster from happening. The U.S. needs more factories. More redundancy. More competition. But building a new drug plant takes 28-36 months in the U.S.-compared to 18-24 months in the EU. Regulatory delays, lack of funding, and low profit margins make it nearly impossible for companies to invest in backup production.

Even with $285 million in new CHIPS Act funding for drug manufacturing, analysts say that’s less than 5% of what’s needed to make a real difference. The market simply doesn’t reward companies for making cheap, essential drugs. Why spend millions to build a plant for a drug that only makes $0.10 per dose when you can make billions on a new cancer pill?

Where Federal Policies Are Falling Short

The 2025-2028 HHS Draft Action Plan lays out four goals: Coordinate, Assess, Respond, Prevent. Sounds good. But implementation is a mess. Only 28 of 50 states have set up the required supply chain mapping systems. Rural hospitals say it takes them six months just to get the software working. The new Coordination Portal, meant to link federal agencies, has a 2.1/5 usability rating from healthcare workers. Meanwhile, the FDA’s public shortage database gets 3,247 reports-but 62% of them are duplicates.

Worse, funding is being cut. The 2026 HHS budget slashes $1.2 billion from FEMA’s emergency response and $850 million from state public health grants. BARDA, the agency that funded breakthrough manufacturing tech like continuous production, lost 22% of its budget. NIH’s drug development funding dropped 18% from 2024 to 2025. Without investment in innovation, the U.S. is just patching leaks while the whole ship sinks.

What’s Happening on the Ground?

Hospitals aren’t waiting for Washington. Pharmacists are working 10+ hours a week just managing shortages. One pharmacist on Reddit described having to compound cisplatin from raw chemicals because the finished drug vanished. Another said they used five different manufacturers for the same drug in a single week.

The American Hospital Association reports hospitals now spend $1.2 million a year on shortage management. 68% have delayed treatments. 42% have had medication errors because of substitutions. Patients are skipping doses-29% of Americans, according to patient advocacy groups. For cancer patients, that number jumps to 68%.

And it’s not just hospitals. The FDA’s Early Notification Pilot Program, which requires manufacturers to report potential shortages six months ahead, cut shortage durations by 28%. But that program is now being scaled back. Why? Because the current administration has weakened reporting rules. The FDA issued only 17 warning letters for non-reporting between 2020-2024. The EU issued 142 under similar rules.

What Could Actually Work?

Experts agree: the U.S. needs three things.

- Second-source manufacturing-forcing companies to build backup production lines. The FDA just started expediting reviews for these, and 14 applications are already in the pipeline. That’s the most promising move in years.

- Financial incentives-paying manufacturers to make low-margin essential drugs. The Drug Shortage Prevention and Mitigation Act proposes Medicare bonuses for hospitals that keep backup supplies. That’s a start, but it’s not enough.

- Transparency-making supply chain data public. If companies knew where the next bottleneck was, they could act before a crisis. Right now, they’re guessing.

The EU’s approach is simpler: require member states to stockpile critical drugs and create a centralized monitoring system. Between 2022 and 2024, that cut shortages by 37%. The U.S. could do the same-but it would require political will, not just executive orders.

Is There Hope?

Yes-but only if the focus shifts from crisis response to long-term prevention. Stockpiling APIs helps in emergencies. But if we keep treating drug shortages like a fire to be put out instead of a building code to be fixed, we’ll keep seeing the same fires over and over.

The FDA’s AI-powered monitoring system, launched in November 2025, predicts shortages with 82% accuracy 90 days ahead. That’s a game-changer-if we use it. If we stop cutting funding, if we reward manufacturers for making essential drugs, if we require redundancy in production, then we might actually stop the shortages before they start.

Right now, the federal response is a patchwork of good ideas and bad execution. The tools are there. The data is there. What’s missing is the commitment to fix the system-not just the symptoms.

Why are drug shortages getting worse despite government action?

Drug shortages are worsening because federal efforts focus on reacting to crises instead of preventing them. While programs like SAPIR help in emergencies, they don’t fix the root causes: too few manufacturers, low profit margins on essential drugs, and lack of redundancy in production. Most shortages come from drugs outside the 26 in the reserve list, and reporting requirements are poorly enforced. Without incentives to build backup factories or penalties for non-compliance, shortages will keep happening.

What is SAPIR, and how does it help with drug shortages?

SAPIR, or the Strategic Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients Reserve, is a federal stockpile of raw drug ingredients-not finished medications. By storing APIs, the government can quickly turn them into drugs during shortages. APIs are cheaper to store, last longer, and are easier to transport than pills or injections. Since August 2025, SAPIR has targeted 26 critical drugs like antibiotics and cancer treatments. It reduces reliance on foreign suppliers, especially China, which produces 80% of U.S. APIs. But it only covers a small fraction of shortage-prone drugs.

Why doesn’t the U.S. just make more drugs domestically?

Making drugs in the U.S. is expensive and slow. Building a new manufacturing facility takes 28-36 months here, compared to 18-24 months in the EU. Plus, many essential drugs-like IV fluids or generic antibiotics-have tiny profit margins. Companies won’t invest millions in a plant that only makes pennies per dose. The market rewards high-priced specialty drugs, not life-saving basics. Without financial incentives or government contracts to guarantee sales, manufacturers have no reason to build domestic capacity.

How do drug shortages affect patients?

Patients are directly harmed. 29% of Americans have skipped doses because a drug wasn’t available. Cancer patients are hit hardest-68% report treatment delays or substitutions. Hospitals have reported treatment delays, medication errors, and increased monitoring needs. Some pharmacists have had to compound drugs from raw chemicals. These aren’t theoretical risks-they’re real, life-altering consequences for people who rely on consistent access to medication.

What’s the difference between the U.S. and EU approaches to drug shortages?

The EU requires member states to maintain mandatory stockpiles and uses a centralized monitoring system run by the European Medicines Agency. Since 2022, this has cut shortages by 37%. The U.S. relies on voluntary reporting, patchwork state programs, and limited federal reserves. The EU also enforces penalties for non-reporting and gives manufacturers clearer rules. The U.S. issued just 17 warning letters for missed reports between 2020-2024; the EU issued 142 under similar rules. The EU’s system is more predictable, transparent, and enforced.

Is the FDA’s AI shortage predictor effective?

Yes, but only if used properly. The FDA’s Enhanced Shortage Monitoring System, launched in November 2025, uses AI to analyze 17 data streams-including shipping records, hospital purchases, and factory output-to predict shortages 90 days in advance with 82% accuracy. That’s a major upgrade from the old system. But its effectiveness depends on whether hospitals and manufacturers actually act on the alerts. Right now, many aren’t trained to use it, and federal agencies aren’t fully integrated with the system. The technology works. The human response doesn’t yet.

What Comes Next?

The next 12 months will be critical. The FDA is reviewing 14 applications for second-source manufacturers-this could add backup supply for 8 high-risk drugs by mid-2026. If those approvals go through, it’s the first real step toward systemic resilience. But without Congress passing legislation that requires redundancy, funds domestic production, and restores mandatory reporting, we’ll be back here in another year.

Hospitals, pharmacists, and patients are already living the crisis. The government has the data, the tools, and the knowledge. What’s missing is the will to do more than just react.

Comments (14)

-

Gloria Ricky February 14, 2026

Yikes, I had no idea how bad this was. My mom’s on chemo and they switched her med 3 times last year-each time she got sick all over again. It’s not just about stockpiles, it’s about people. We’re treating medicine like it’s a commodity, not a lifeline. 😔

-

Stacie Willhite February 16, 2026

I work in a rural clinic. We’ve had to ration saline for weeks. No one talks about how the nurses are the ones holding it all together. They’re not just pharmacists-they’re problem solvers with duct tape and hope. We need real support, not just press releases.

-

Jason Pascoe February 17, 2026

Interesting take. I’m from Australia-we’ve got our own supply chain mess, but our national system forces manufacturers to maintain backup production. It’s not perfect, but it’s structured. The U.S. keeps trying to innovate around the problem instead of just building the damn infrastructure. Why does everything have to be so reactive here?

-

Sonja Stoces February 18, 2026

OMG this is all just a Big Pharma scam 😤 SAPIR? More like SAPIR-‘Stockpile And Profit Immediately Reserve’. They’re using ‘foreign dependence’ as an excuse to jack up prices. I bet the same CEOs who profit from shortages are the ones pushing these ‘solutions’. 🤡

-

Annie Joyce February 19, 2026

Let’s be real-the real villain here isn’t China, it’s the profit motive. You can’t expect companies to build factories for drugs that make 10 cents a dose when they can make millions off a new $100K pill. It’s like asking a baker to bake bread for free while they’re busy selling caviar cupcakes. We need to pay for the basics like we pay for luxury. Period.

And don’t get me started on how the FDA’s AI tool is collecting data but no one’s trained to use it. It’s like giving a Ferrari to someone who’s never driven a bicycle. The tech’s there. The will? Not even close.

Also-why is no one talking about the fact that 68% of cancer patients skip doses? That’s not a statistic. That’s a moral failure. We’re letting people die because we’re too cheap to fix a broken system.

-

Rob Turner February 19, 2026

It’s funny-we’ve got AI predicting shortages 90 days out, yet we’re still arguing about whether to fund backup plants. We’ve got the knowledge. We’ve got the tools. We just lack the collective will to act like adults. The EU’s system isn’t magic-it’s just consistent. No drama. No politics. Just rules. Maybe we need to stop thinking of healthcare as a market and start treating it like infrastructure. Like roads. Like water. You don’t wait for a flood to build a dam.

-

Luke Trouten February 21, 2026

The deeper issue here is our cultural aversion to systemic thinking. We love heroic fixes-like stockpiling APIs-but hate the boring, slow work of regulation, incentive design, and long-term investment. We’d rather have a flashy solution than a stable one. It’s why we keep having the same fires. We’re addicted to crisis response because it feels like action. But real prevention? That’s just… work.

And yet, we’re the country that landed on the moon. We can fix this. We just have to stop pretending that a stockpile is a strategy.

-

Gabriella Adams February 23, 2026

Dear Government: You have a predictive AI system with 82% accuracy. You have data. You have funding. You have international examples. You have the mandate. So why are you still pretending this is a supply issue? It’s a values issue. You value profits over people. Until that changes, no API reserve, no AI, no executive order will matter.

-

Joanne Tan February 23, 2026

Wait so you’re saying we need more factories? Like… actual buildings? With people? In the US? 😅 I thought we were just gonna 3D print insulin now. Jk… but seriously, why is this so hard? We can build rockets but not a drug plant? What’s the holdup??

-

Carla McKinney February 25, 2026

Everyone’s acting like this is new. Newsflash: this has been happening since 2010. The FDA’s been asleep at the wheel. The ‘new’ programs are just PR. The real solution? Fire every bureaucrat who’s been in charge since 2015 and start over. This isn’t policy-it’s negligence dressed up as innovation.

-

Ojus Save February 26, 2026

lol i read this whole thing and still dont get it. why cant we just print more pills? its not rocket science

-

Jack Havard February 27, 2026

Who says the shortages aren’t intentional? Think about it. If there’s no supply, people pay more. If people pay more, companies get richer. The whole thing’s a racket. The government’s not fixing it-they’re protecting the system. Wake up.

-

Kristin Jarecki February 28, 2026

Thank you for this meticulously detailed analysis. The disconnect between policy and practice is not merely administrative-it is existential. The structural disincentives for domestic manufacturing are not accidental; they are systemic. The EU’s centralized, enforceable model demonstrates that regulatory clarity, coupled with financial accountability, yields measurable outcomes. The United States, by contrast, continues to prioritize rhetorical innovation over institutional integrity. Until we align incentives with human outcomes-not corporate margins-we will continue to fail those who depend on us most.

-

Jonathan Noe March 1, 2026

Okay but let’s talk about the real hero here: the pharmacist who compounds cisplatin from scratch. That’s not a job. That’s a superpower. We need to pay them like surgeons. We need to give them bonuses. We need to put their faces on billboards. If we’re gonna rely on people to literally make medicine out of thin air, we better start treating them like the frontline warriors they are.