Every time you pick up a packaged food, you’re making a life-or-death decision if you or someone in your family has a food allergy. The label might say ‘Contains: Milk,’ but is that cow’s milk? Goat’s milk? And what about that ‘May contain traces of nuts’ note-does it mean anything real, or is it just legal cover? In 2025, the rules changed. The FDA’s new guidance isn’t just a tweak-it’s a rewrite of how allergens are named, declared, and controlled on food labels. For the 32 million Americans with food allergies, including 5.6 million kids, this matters more than ever.

What’s Actually in Your Food Now?

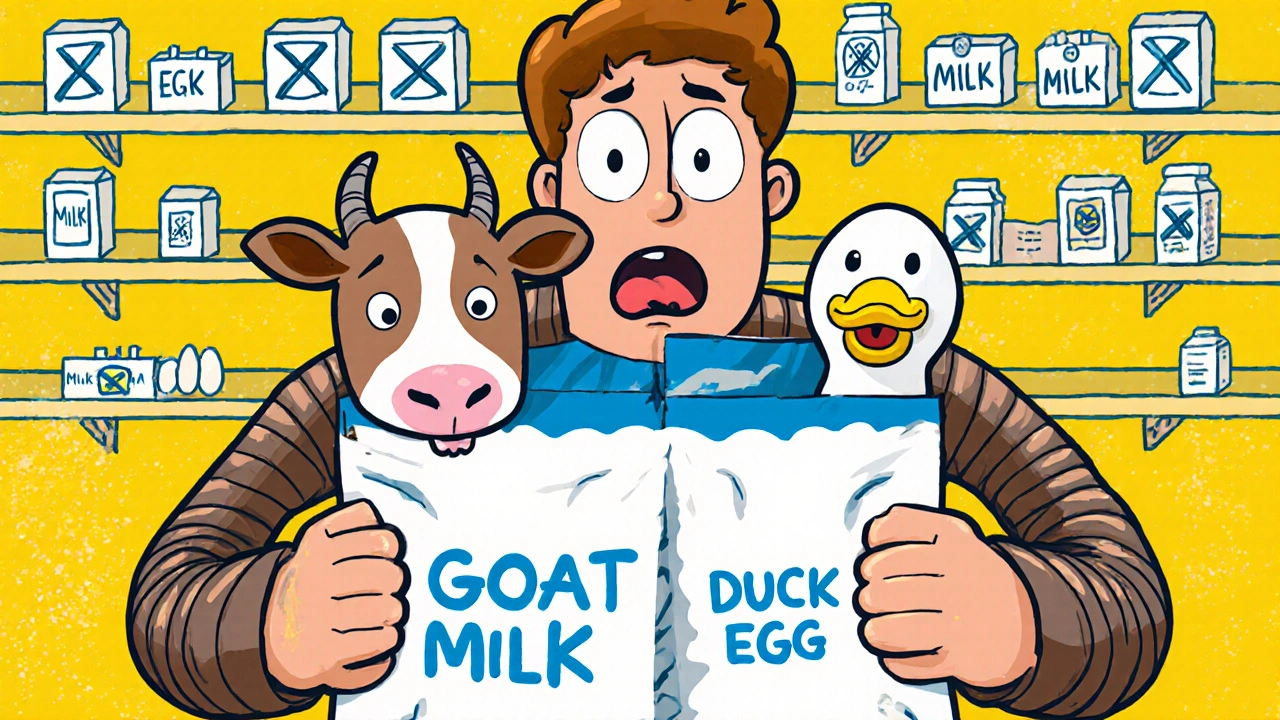

Before 2025, a label could just say ‘egg’ or ‘milk.’ That was it. But if you’re allergic to duck eggs or goat milk, you had to call the manufacturer, hope they answered, and pray they knew the answer. Now, the FDA requires exact sources. If it’s goat milk, the label must say ‘goat milk.’ If it’s duck egg, it can’t just say ‘egg’-it must say ‘duck egg.’ Same for fish: you can’t just say ‘fish.’ You have to specify if it’s trout, shark, or lamprey eel. This isn’t bureaucracy-it’s survival.Why? Because allergies aren’t one-size-fits-all. A person might react to cow’s milk but safely eat goat’s milk. Another might tolerate chicken eggs but go into anaphylaxis from quail eggs. Before, these distinctions were hidden. Now, they’re required. That means parents shopping for their kids can finally make safe choices without guesswork.

The Big Changes: What Got Removed, Added, or Split

Some changes surprised even long-time allergy advocates. Coconut was removed from the list of tree nuts. For years, people with tree nut allergies avoided coconut because labels grouped them together. But coconut is a fruit, not a nut. Only 0.04% of the population is allergic to it-far fewer than those allergic to almonds or walnuts. Removing it from the major allergen list means people with tree nut allergies can now safely eat coconut milk, oil, or flakes without fear.Shellfish got split, too. Only crustaceans-like shrimp, crab, and lobster-are now covered under the ‘shellfish’ label. Mollusks like oysters, clams, scallops, and mussels? They’re not included. That’s a problem. About 1.5 million Americans are allergic to mollusks, and many didn’t realize they were at risk because they were told to avoid ‘shellfish.’ Now, those products can legally say ‘no shellfish’ while still containing oysters. That’s a dangerous gap.

And then there’s sesame. Added as the ninth major allergen in 2023 under the FASTER Act, it’s now required to be clearly labeled. But many products still slip through. If you see ‘natural flavors’ or ‘spices’ and you’re allergic to sesame, you’re still playing Russian roulette. The new guidance says manufacturers must list sesame by name-even if it’s in a spice blend. No more hiding behind vague terms.

‘Free-From’ vs. ‘May Contain’-You Can’t Have Both

One of the most confusing parts of food labels has been the contradiction between ‘gluten-free’ or ‘milk-free’ claims and ‘may contain milk’ warnings. You’d see a product labeled ‘dairy-free’ on the front, then on the back: ‘Processed in a facility that also handles milk.’ Which one do you trust? The FDA’s 2025 guidance says: you can’t have both.If a product claims to be free of an allergen, it must be free-not just mostly free. That means no cross-contact. No shared equipment. No airborne particles. If there’s any risk of contamination, the manufacturer can’t use ‘free-from’ language. They can only use advisory statements like ‘may contain,’ and even then, those statements must be truthful. No more misleading marketing. If you’re buying ‘peanut-free’ granola, you should be able to believe it.

This change was pushed hard by Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE). Their research showed that families were avoiding products labeled ‘may contain’ even when they didn’t need to-because they couldn’t trust the ‘free-from’ claims. Now, if a company says ‘no soy,’ and you see ‘may contain soy’ on the same package, that’s a violation.

What About Cross-Contact? Is It Even Regulated?

Cross-contact happens when a tiny bit of an allergen gets into a food that wasn’t meant to have it. A spoon used for peanut butter gets washed and then used for jelly. A conveyor belt that runs almonds then runs pretzels. These aren’t always preventable, but they’re dangerous.The FDA says advisory labeling for cross-contact is still voluntary. That means companies can choose to write ‘may contain tree nuts’ or they can skip it entirely. But if they do write it, they can’t lie. If there’s no chance of cross-contact, they can’t add ‘may contain’ just to cover their legal bases. And if they claim a product is ‘allergen-free,’ they must prove they’ve taken steps to prevent cross-contact-through cleaning protocols, equipment separation, and testing.

Small manufacturers struggle with this. A family-owned bakery might not have the budget for dedicated nut-free ovens or allergen testing kits. The FDA guidance doesn’t require compliance-it’s just advice. But liability is real. If someone gets sick, and the label said ‘nut-free’ but there was cross-contact, the company could be sued. So many are choosing to comply anyway.

Who’s Affected-and Who’s Still at Risk

The new rules help millions. Parents of kids with cow’s milk allergies can now shop without calling every brand. People allergic to sesame can finally spot it in sauces, dressings, and hummus. But not everyone benefits.Mollusk-allergic people are now in a gray zone. If you’re allergic to clams, you can’t rely on a label to warn you. You have to read every ingredient list carefully-and even then, you might miss it. The same goes for people allergic to less common allergens like mustard, celery, or lupin. These aren’t covered under U.S. law. The FDA is studying them, but right now, they’re invisible on labels.

And then there’s alcohol. Wine, beer, and spirits aren’t regulated by the FDA-they’re under the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB). TTB doesn’t require allergen labeling at all. So a wine made with egg whites for clarification? A beer brewed with milk sugar? No label. No warning. Just a bottle with no clue.

What You Can Do Right Now

The system is better-but still imperfect. Here’s how to stay safe:- Always read the full ingredient list, not just the ‘Contains’ statement.

- Look for specific sources: ‘goat milk,’ ‘duck egg,’ ‘shrimp,’ not just ‘milk’ or ‘shellfish.’

- Never trust ‘free-from’ claims if you also see ‘may contain’ on the same package.

- If a product doesn’t list sesame, assume it might be there-especially in ethnic foods, sauces, or baked goods.

- When in doubt, call the manufacturer. Ask: ‘Is this product made on shared equipment with [allergen]?’

- For mollusk allergies, avoid seafood markets and pre-packaged seafood blends unless you can confirm the exact ingredients.

- For alcohol, assume all wines and beers could contain hidden allergens unless labeled otherwise.

Also, keep a food diary. Note what you ate, what the label said, and if you had a reaction. That data helps you-and others-spot patterns. The FDA doesn’t track every reaction, but your experience can help push for change.

The Future: What’s Coming Next

The FDA says this guidance ‘may be updated as new scientific evidence emerges.’ That’s code for: more allergens are coming. Mustard, celery, and sesame are already under review. The global food allergen testing market is growing fast-projected to hit $1.4 billion by 2029. That means better testing, better labels, and eventually, stricter rules.By 2027, experts predict 75% of major U.S. food companies will follow these new standards voluntarily. Why? Because consumers demand it. And because lawsuits cost more than compliance.

But enforcement is still weak. The FDA inspects only about 10% of food plants each year. That means a lot of labels aren’t checked. That’s why your vigilance matters. You’re not just reading a label-you’re protecting your life.

The system is improving. But safety doesn’t come from government rules alone. It comes from knowing what to look for-and never letting a vague label off the hook.

Are coconut and sesame both considered tree nuts on food labels in 2025?

No. As of 2025, coconut is no longer classified as a tree nut on U.S. food labels. It’s now treated as a fruit, and manufacturers don’t need to list it under tree nuts. Sesame, however, is now a separate major allergen and must be clearly labeled by name-whether it’s in spices, sauces, or baked goods.

Can a product say ‘milk-free’ and also say ‘may contain milk’ on the same label?

No. Under the FDA’s 2025 guidance, a product cannot make a ‘free-from’ claim like ‘milk-free’ if it also includes an advisory statement like ‘may contain milk.’ The two statements contradict each other. If a product claims to be free of an allergen, it must be free of that allergen-even in trace amounts from cross-contact.

What shellfish are covered under the new labeling rules?

Only crustacean shellfish are covered: shrimp, crab, and lobster. Mollusks like oysters, clams, scallops, and mussels are no longer included under the ‘shellfish’ allergen label. This means products containing mollusks don’t need to warn consumers about them-even if they’re a known allergen for 1.5 million Americans.

Do alcohol labels have to list allergens like milk or eggs?

No. Alcoholic beverages are regulated by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), not the FDA. TTB does not require allergen labeling. So wines clarified with egg whites or beers brewed with milk sugar can legally contain these allergens without any warning on the label.

Why does the FDA require specific sources like ‘goat milk’ instead of just ‘milk’?

Because many people are allergic to one type of animal milk but can safely consume others. For example, someone might react to cow’s milk but tolerate goat or sheep milk. Before 2025, consumers had to contact manufacturers to find out the source. Now, the source must be clearly stated-making it safer and easier for people to make informed choices.

Comments (13)

-

Mark Kahn November 20, 2025

Finally! I’ve been calling manufacturers for years just to ask if their ‘milk’ is cow or goat. My kid reacts to cow but eats goat cheese like it’s candy. This change is life-changing. Thank you, FDA.

-

Daisy L November 20, 2025

Oh, so now we’re playing ‘Guess the Animal’ with our groceries?! Coconut’s not a nut? What’s next-‘butter’ means cow butter only? And who decided mollusks aren’t shellfish?! This is bureaucratic madness wrapped in a ‘safety’ bow! I’m not trusting ANY label anymore!

-

Anne Nylander November 22, 2025

Yessss!! This is huge for families like mine!! I used to stress over every snack. Now I can actually read the label and feel safe. No more guesswork!! Thank you for making this happen!! 😊

-

Clifford Temple November 23, 2025

They’re letting sesame slip through in ‘spices’? That’s a joke. And who’s letting ‘may contain’ slide? This isn’t safety-it’s corporate cowardice. We need mandatory testing, not suggestions. The FDA’s asleep at the wheel.

-

Corra Hathaway November 25, 2025

Coconut off the tree nut list? YES!! I’ve been eating coconut oil for years thinking I was risking my life 😅 And sesame? FINALLY. But… alcohol still doesn’t have to say ‘egg whites’?? Come on. 😒

-

Shawn Sakura November 26, 2025

It's important to note that while the FDA has issued guidance, compliance is not mandatory for all manufacturers. Many small producers lack the resources to implement full allergen testing. Still, the clarity on labeling is a significant step forward. Always verify with the manufacturer when in doubt.

-

Paula Jane Butterfield November 28, 2025

As someone who grew up in a household with multiple food allergies, this is the most meaningful update I’ve seen in decades. But I worry about immigrants and non-native speakers-many won’t understand ‘duck egg’ vs ‘chicken egg.’ We need multilingual labels too. This helps, but it’s not enough.

-

Julia Strothers November 29, 2025

Let’s be real-this is all a distraction. The FDA’s pushing these labels because Big Pharma wants you to buy more EpiPens. Coconut was removed because they’re pushing coconut oil as a ‘superfood.’ Mollusks? They’re hiding it because the fishing industry lobbied hard. This isn’t safety-it’s corporate manipulation. Wake up.

-

Erika Sta. Maria November 30, 2025

But… if coconut is a fruit, then why do Ayurvedic texts classify it as a nut? And if sesame is now a major allergen, why isn’t turmeric? It’s cross-reactive in 12% of cases! You’re all missing the deeper truth: allergens are a construct of Western medicine. In India, we’ve managed for centuries without labels. Why are we now obsessed with categorization?

-

Nikhil Purohit November 30, 2025

Actually, the FDA’s 2025 guidance is binding for all interstate food manufacturers, not just advice. The confusion comes from the fact that intrastate producers (small local bakeries, etc.) are exempt. But if you buy packaged food from a national brand, the rules apply. And yes, ‘may contain’ still isn’t regulated-only if it’s false.

-

Leo Tamisch December 1, 2025

How quaint. We’ve moved from ‘milk’ to ‘goat milk’-as if that somehow elevates the human condition. The real tragedy? We’ve outsourced our intuition to regulatory labels. A society that needs a 200-word disclaimer to eat a granola bar has already lost its way. 🤷♂️

-

Franck Emma December 2, 2025

They forgot the worst part: wine with egg whites. No label. No warning. Just a bottle. My friend died from that. And now they’re proud of ‘goat milk’? Pathetic.

-

Paula Jane Butterfield December 3, 2025

Paula here-just wanted to reply to @NikhilPurohit. You’re right about the global gap. In India, mustard and celery are major allergens and labeled. The U.S. is behind. We need to push for global harmonization. Maybe the WHO can help. This shouldn’t be country-by-country guesswork.