Many people assume the FDA has the power to force a drug company to pull a dangerous medicine off the shelves. That’s not true. Not really. The FDA can’t just order a recall like a police officer ordering a car off the road. Instead, it asks. And when a company refuses? That’s when things get complicated.

How the FDA Actually Removes Unsafe Drugs

The FDA’s power over drug recalls comes from the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), passed in 1938. Under this law, drug manufacturers are responsible for the safety of their products. If a problem is found-like contamination, mislabeling, or unexpected side effects-the FDA contacts the company and requests a voluntary recall. In over 99% of cases, the company agrees. Why? Because fighting the FDA is expensive, risky, and bad for business.

Think of it like this: the FDA doesn’t have a sledgehammer. It has a loudspeaker. It tells the company: “Your drug is dangerous. If you don’t recall it, we’ll go to court and shut you down.” Most companies choose to recall. They know a lawsuit could cost millions and destroy their reputation. In 2022, out of 4,312 drug recalls, only three required legal action from the FDA. That’s 0.07%.

But here’s the catch: when a company says no, the FDA has to go to federal court and ask a judge to issue an injunction. That process can take weeks. During that time, unsafe drugs keep being sold. In 2018, when NDMA-a known carcinogen-was found in blood pressure meds like valsartan, it took six months for all contaminated lots to be fully pulled from the market. Why? Because some manufacturers, especially overseas, dragged their feet. The FDA couldn’t force them. It could only wait, warn, and plead.

The Three Levels of Drug Recalls

Not all recalls are created equal. The FDA classifies them into three categories based on how dangerous the drug is:

- Class I: The most serious. These drugs could cause serious injury or death. Examples: pills with too much active ingredient, contaminated injectables, or drugs with undeclared allergens. In 2022, only 2.1% of recalls fell into this category.

- Class II: These may cause temporary or reversible health problems. Think: wrong label, missing instructions, or a batch with slightly off potency. This is the most common type-68.7% of all recalls in 2022.

- Class III: The least dangerous. These won’t hurt you, but they break rules. Maybe the bottle says “take with food” when it shouldn’t, or the expiration date is smudged. These make up about 29.2% of recalls.

The depth of the recall depends on the class. For a Class I recall, hospitals and pharmacies must track down every single patient who got the drug. For a Class III, they might just need to notify distributors. The FDA doesn’t dictate how far the recall goes-it’s up to the company, with FDA guidance.

How a Recall Starts

Recalls don’t usually happen because someone got sick. They start because someone noticed something odd.

Manufacturers are required to test their drugs for stability at least once a year. If a batch starts degrading faster than expected, they must report it. Sometimes, a pharmacist notices a strange smell or color in a pill. A hospital pharmacist might spot a pattern of side effects. Or, the FDA’s own monitoring system, MedWatch, picks up a spike in adverse event reports. In 2022 alone, MedWatch received over 1.2 million reports.

Once a problem is confirmed, the manufacturer must notify the FDA within 24 hours. Then, they have to submit a “Recall Strategy”-a plan that answers: Who got this drug? How do we reach them? How do we get it back? What’s the risk? The FDA reviews this plan and may ask for changes.

Why Devices Are Different

Here’s where it gets interesting: the FDA can force recalls on medical devices. That’s because of the Medical Device Amendments of 1976. If a pacemaker, insulin pump, or surgical tool poses a serious health risk, the FDA can issue a mandatory recall order under 21 CFR 810.

Why the difference? It’s history. When the FD&C Act was written in 1938, drugs were simpler. Devices weren’t as complex. By 1976, when devices like artificial hearts and MRI machines were becoming common, Congress gave the FDA stronger tools for them. Drugs? Still stuck with the old rules.

This creates a dangerous gap. A faulty heart valve can be pulled immediately. But a contaminated antibiotic? The FDA has to wait. Critics say this is outdated. Dr. Sidney Wolfe of Public Citizen called it a “critical vulnerability” in 2019. He pointed to the valsartan recall as proof: delays cost lives.

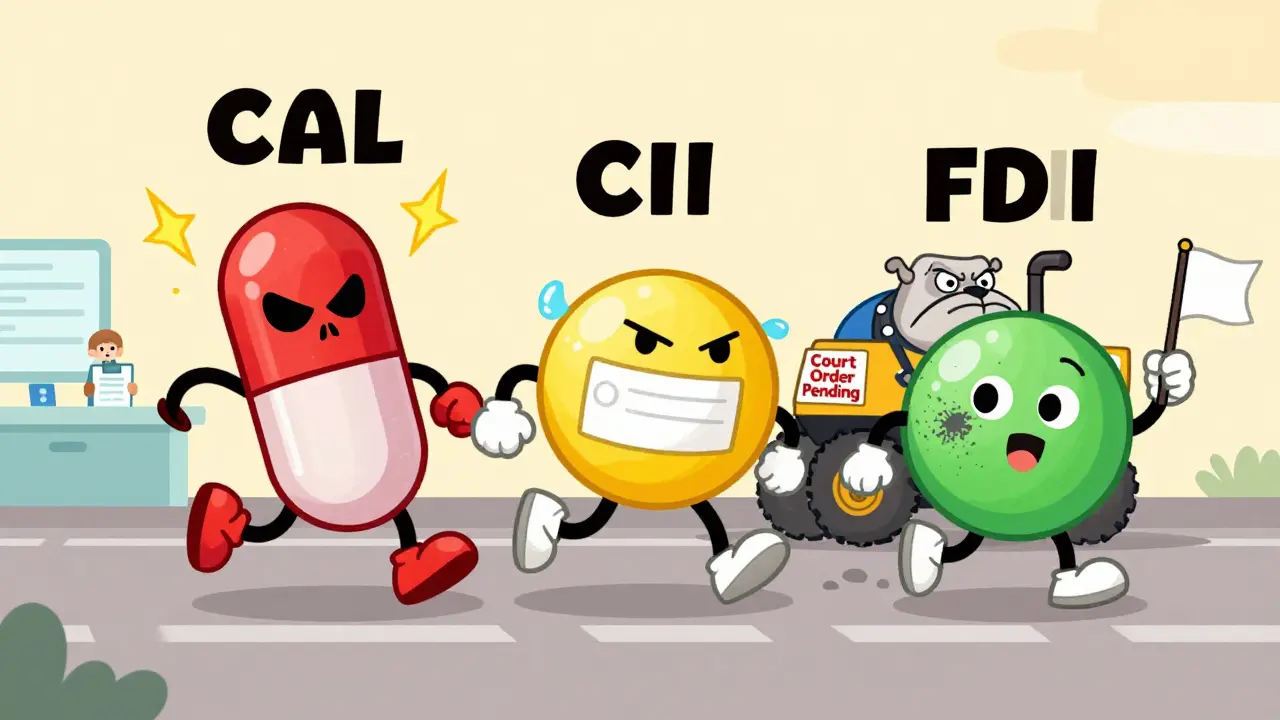

Who’s Pushing for Change?

There’s been a push to give the FDA mandatory recall power for drugs. The FD&C Modernization Act of 2022 included a section-Section 604-that would have done exactly that. But it was removed during committee review. Why? Lobbying.

PhRMA, the pharmaceutical industry’s main trade group, spent $8.2 million in the second quarter of 2023 alone to fight mandatory recall provisions. They argue that voluntary recalls work: 99.98% effective over the last decade. And they’re right-most recalls happen quickly. But that 0.02%? That’s where people die.

On the other side, patient safety groups like the Center for Science in the Public Interest and the Hemophilia Federation argue that the system is too slow. They point to biologics-complex drugs made from living cells-as the next big risk. Contamination in these drugs is harder to detect and more dangerous. Waiting for a company to act isn’t enough.

What Hospitals and Pharmacies Do

When a recall hits, it’s not just the FDA’s job. Hospitals, pharmacies, and clinics have to act fast. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) says every pharmacy should have a 12-point recall plan:

- Assign someone to monitor recall notices daily

- Keep a central database of all drug lots received

- Train staff on how to respond

- Notify patients immediately for Class I recalls

- Document every step taken

- Work with manufacturers to get replacement drugs

But it’s messy. A 2022 ASHP survey found that 68% of hospital pharmacies struggle to match recalled lots with patient records because manufacturers use inconsistent labeling. One pharmacy might get a recall notice for “Lot 2210A,” but their system only has “2210-A.” That’s a 3.7-day delay in patient notification on average.

That’s why a $287 million industry has grown around recall tracking. Companies like Recall Masters and Recall Index sell software to hospitals that automatically cross-reference recall notices with their inventory and patient records. They’re not optional anymore-they’re essential.

What You Can Do

If you take prescription medication, here’s how to protect yourself:

- Keep your pill bottles. Don’t throw them away until you’ve finished the prescription. The lot number is your lifeline.

- Sign up for FDA recall alerts at fda.gov/medwatch. You’ll get emails when your drug is recalled.

- Ask your pharmacist: “Has my medication been recalled?” Don’t assume they know.

- If you feel something’s wrong with your pill-strange smell, odd color, unexpected side effect-call your doctor and report it to MedWatch.

Most recalls are handled quietly and quickly. But when they’re not, it’s because the system is built on trust-not power. And trust can break.

What’s Next?

The proposed PREVENT Pandemics Act (S.2871), introduced in late 2023, includes Section 3103-which would give the FDA the power to order mandatory drug recalls. If it passes, it would be the biggest change to drug safety law in decades.

But industry opposition is strong. And the FDA still operates under 1938 rules. Until then, the system relies on companies doing the right thing. Most do. But when they don’t? The FDA can only wait.

Comments (15)

-

Eileen Reilly January 13, 2026lol so the FDA is just begging drug companies not to kill people? 🤡

-

Alex Fortwengler January 14, 2026This is why I don't trust anything made in China or India. They're just waiting for the FDA to say "please" before they poison grandma with fake pills. 0.07%? That's 300 people dead a year and nobody cares.

-

Monica Puglia January 15, 2026I just checked my blood pressure med-lot number matches the recall from last year. I'm calling my pharmacist tomorrow. 😅 thanks for the heads up, this stuff matters.

-

Jose Mecanico January 16, 2026I work in hospital pharmacy and this is 100% accurate. We get recall notices daily. The software we pay $15k/year for still messes up lot numbers half the time. It's a mess. The FDA doesn't have the power to fix it, and the companies won't help us fix it either.

-

Sonal Guha January 17, 2026Class III recalls are just corporate paperwork exercises no one takes seriously

-

Prachi Chauhan January 18, 2026The system is built on trust because capitalism prefers convenience over safety. We let companies police themselves because it's cheaper than regulating them. That's not oversight. That's negligence dressed up as efficiency.

-

Alice Elanora Shepherd January 18, 2026I'm curious-why is it that medical devices, which can be life-or-death in milliseconds, get mandatory recalls, but a contaminated antibiotic, which can kill over days or weeks, doesn't? It feels like the law is written for the technology of 1938, not the reality of 2024.

-

Faith Wright January 19, 2026I used to think the FDA was a shield... now I see it's a polite suggestion box. And the people who get hurt? They're not the ones writing the laws. They're the ones holding the pill bottle with the smudged expiration date.

-

Jay Powers January 19, 2026I get why the industry resists mandatory recalls-it's scary. But the fact that we're still debating this in 2024? That's the real scandal. We don't need more studies. We need more power for the FDA. Period.

-

Rebekah Cobbson January 20, 2026If you take meds, keep your bottles. Seriously. I lost my mom because we didn't know her heart med was recalled until she was already in the hospital. It's not paranoia-it's survival.

-

Christina Widodo January 22, 2026Wait so if a device like a pacemaker can be forcibly recalled but a drug can't... does that mean a faulty heart valve is considered more dangerous than a cancer-causing pill? That doesn't make sense.

-

Abner San Diego January 23, 2026The FDA doesn't have power because the corporations own Congress. It's not about safety-it's about profit. And the people who die? They're just collateral damage in the grand scheme of quarterly earnings. Wake up.

-

Audu ikhlas January 23, 2026America thinks it's the best but can't even force a company to pull poison off shelves? My country has stricter rules than this. We don't wait for companies to be nice. We make them obey.

-

Lawrence Jung January 23, 2026The real tragedy isn't the recall system-it's that we've normalized this. We accept that someone will die because a corporation didn't feel like being responsible. We don't demand change because we've been taught to trust institutions. But institutions don't care. People do.

-

jordan shiyangeni January 25, 2026The entire pharmaceutical industry is a Ponzi scheme built on the illusion of safety. The FDA doesn't regulate-it rubber-stamps. Every recall is a confession: they knew. They just didn't care until someone died. And now they're lobbying harder than ever to keep the status quo. The only thing more dangerous than a bad drug? The system that lets it happen.