Why Your Allergy Medicine Could Be Putting You at Risk Behind the Wheel

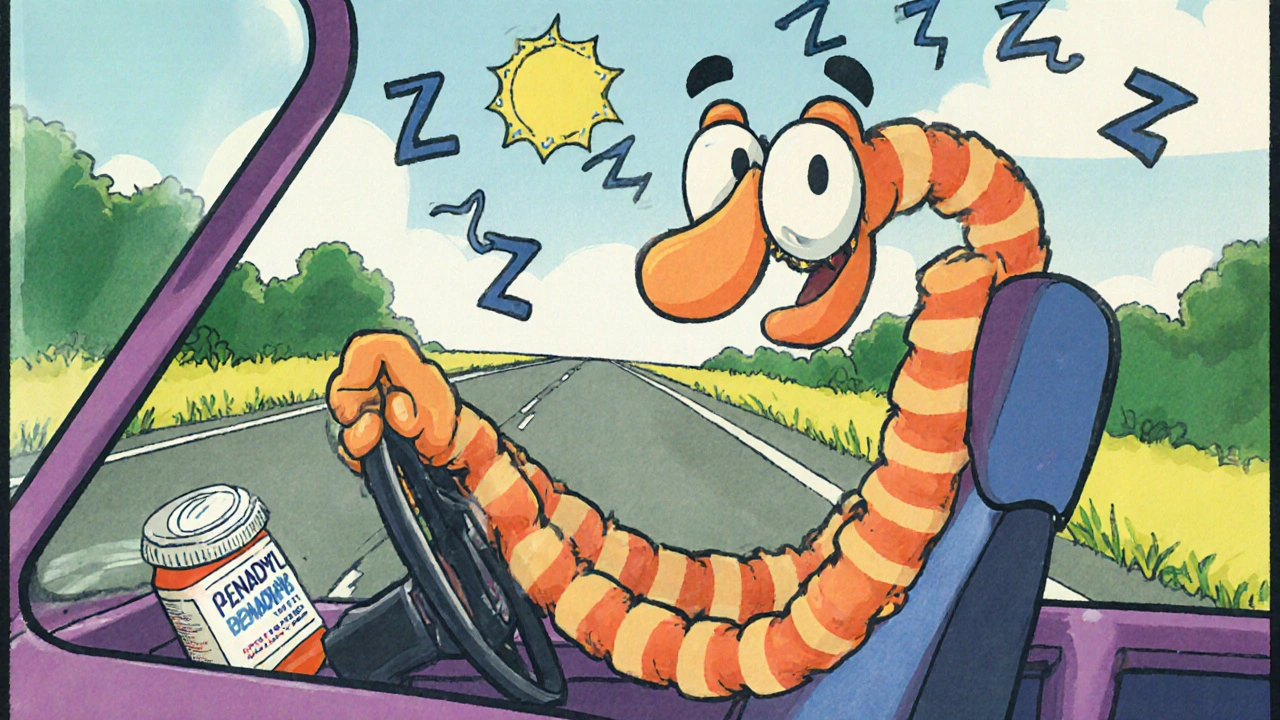

You take an antihistamine to stop your sneezing, itchy eyes, or runny nose. You feel fine. So you get in the car and drive to work, the grocery store, or your kid’s soccer game. But here’s the truth: antihistamines can slow your reactions, blur your focus, and make you as dangerous on the road as someone with a blood alcohol level of 0.08%-even if you don’t feel drunk.

It’s not just a myth. In 2022, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration found that nearly 1 in 6 medication-related traffic violations involved antihistamines. That’s tens of thousands of drivers each year who think they’re safe, but aren’t. And the worst part? Most of them are taking over-the-counter pills they assume are harmless.

The Three Generations of Antihistamines-And Why It Matters

Not all antihistamines are the same. They’re grouped into three generations based on how they affect your brain. The difference isn’t just scientific-it’s life-or-death when you’re behind the wheel.

First-generation antihistamines include diphenhydramine (Benadryl), chlorpheniramine, and clemastine. These were designed decades ago to block histamine, but they also slip easily into your brain. That’s why they make you drowsy. In driving simulators and real-road tests, people who took these drugs showed 30-50% more lane drifting than those who didn’t. That’s the same level of impairment as being legally drunk in most U.S. states.

Second-generation antihistamines like cetirizine (Zyrtec) and loratadine (Claritin) were created to be less sedating. But “less” doesn’t mean “none.” Studies show cetirizine at the standard 10mg dose causes mild but measurable slowing in reaction time for 15-20% of users. Loratadine is safer for most, but not everyone. Some people-especially older adults or those taking other meds-still feel foggy.

Third-generation antihistamines like fexofenadine (Allegra) and levocetirizine (Xyzal) are the current gold standard for drivers. They barely cross into the brain. In over 16 controlled driving studies, these drugs showed no difference in performance compared to a placebo. No increased lane deviation. No slower reaction times. No increased crash risk.

The Hidden Dangers: Alcohol, Tolerance, and the Myth of Feeling Fine

Here’s something even more dangerous: mixing antihistamines with alcohol. A single drink with diphenhydramine doesn’t just add to the drowsiness-it multiplies it. Studies show the combination can increase impairment by 200-300%. That’s not just risky. It’s reckless.

Another myth? “I’ve been taking Benadryl for years. I don’t feel sleepy anymore.” That’s called tolerance. And it’s misleading. Yes, you might stop feeling drowsy after a few days. But your brain is still impaired. Research shows even after five days of daily use, drivers still perform 15-20% worse than normal. You think you’re fine. Your body says otherwise.

And here’s the kicker: 70% of people who take first-generation antihistamines can’t accurately tell if they’re impaired. You don’t feel tired? Doesn’t mean you’re safe. The brain doesn’t always recognize its own slowdown. That’s why the Ford Driving Skills for Life program warns: “You may experience slower reaction time, haziness, or mild confusion even if you don’t feel drowsy.”

What the Law Says-And What You Might Not Realize

In the U.S., there’s no blanket law that says “don’t drive after taking antihistamines.” But that doesn’t mean you’re protected.

If you’re in a crash and toxicology shows diphenhydramine in your system, you can be charged with reckless driving, DUI, or even vehicular manslaughter-even if your blood alcohol level is zero. Courts don’t care if you thought it was “just an allergy pill.” They care about impairment.

Some states are catching up. In Europe, 22 countries ban driving for 8-12 hours after taking first-gen antihistamines. Fourteen classify them as controlled substances for drivers. In the U.S., while federal law doesn’t regulate it, some states use medication impairment as aggravating evidence in traffic cases.

And here’s the legal trap: over-the-counter labels often say “may cause drowsiness” in tiny print. Prescription labels are clearer. But most people never read them. Or they assume “non-drowsy” on the box means “safe to drive.” That’s not true.

What You Should Do-Practical Steps for Safe Driving

So what’s the solution? It’s not about giving up allergy relief. It’s about choosing smarter.

- Switch to third-generation antihistamines. Fexofenadine (Allegra) and levocetirizine (Xyzal) are your best options. They work just as well for allergies, with almost zero driving risk.

- Never mix with alcohol. Even one beer with Benadryl can turn a short drive into a dangerous gamble.

- Wait 48 hours after starting any new antihistamine. Test it at home first. Do chores, read, walk around. If you feel even slightly off, don’t drive.

- Take nighttime doses if you must use sedating ones. If you need diphenhydramine, take it right before bed. Don’t take it before your morning commute.

- Check labels carefully. Look for diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine, or doxylamine. These are the big red flags. Avoid them if you drive regularly.

And if you’re unsure? Ask your pharmacist. They see this every day. They can tell you if your allergy pill is safe for driving-or if it’s a hidden hazard.

Real Stories: What Happens When People Ignore the Warning

One Reddit user, “AllergySufferer2020,” wrote: “Took Benadryl before a road trip and had to pull over three times because I kept nodding off-never doing that again.” That’s a lucky one. Others aren’t.

Police reports from traffic accidents in Texas and Florida show a pattern: drivers who took over-the-counter allergy meds before hitting the road, didn’t feel tired, but drifted into other lanes or failed to stop in time. In one case, a man took Benadryl for seasonal allergies, then rear-ended a stopped car at a red light. His blood test showed high levels of diphenhydramine. He wasn’t drunk. He wasn’t texting. He just didn’t know his medicine was making him unsafe.

On the flip side, users of fexofenadine report far fewer issues. In a 2023 Drugs.com survey of over 1,200 people, 82% said they noticed no impact on driving. The rest reported only mild, occasional lapses in concentration-not enough to cause accidents.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters Beyond Your Own Safety

This isn’t just about you. It’s about everyone sharing the road with you.

Studies estimate that if everyone switched to third-generation antihistamines, the U.S. could prevent 5,000-7,000 traffic injuries each year. That’s thousands of families spared from loss. Thousands of hospital visits avoided. Thousands of insurance claims prevented.

And the trend is moving in the right direction. In 2022, 78% of U.S. allergists prescribed fexofenadine or levocetirizine as first-line treatment for patients who drive. The market is shifting-fexofenadine now makes up 38% of the U.S. antihistamine market, up from just 12% in 2000.

The only real barrier? Cost. First-gen antihistamines cost around $4 a month. Third-gen can run $35. But many pharmacies offer generics for under $10. And many insurance plans cover them. It’s worth asking.

What’s Next? Better Medicines, Better Warnings

The science is evolving. In 2021, the FDA approved levocabastine nasal spray-effective for allergies, with zero measurable impact on driving. Seven new peripherally-acting antihistamines are in late-stage trials, promising even fewer side effects.

Regulators are also catching on. The European Medicines Agency now requires all antihistamine labels to clearly state driving risk based on generation and chemical class. The American Medical Association recommends doctors screen patients for antihistamine use during driver’s license evaluations.

It’s not about fear. It’s about awareness. You don’t have to suffer through allergies. You just need to choose the right tool for the job.

Can I drive after taking Benadryl?

No. Benadryl contains diphenhydramine, a first-generation antihistamine that causes significant drowsiness and impairs reaction time, coordination, and alertness. Even if you feel fine, your driving ability is likely reduced. Studies show it can impair you as much as a blood alcohol level of 0.05-0.08%. Avoid driving for at least 6-8 hours after taking it, and never combine it with alcohol.

Is Zyrtec safe to take before driving?

Cetirizine (Zyrtec) is a second-generation antihistamine that’s less sedating than Benadryl, but it’s not risk-free. About 15-20% of users experience measurable driving impairment, especially at higher doses or if they’re sensitive to sedatives. If you’ve never taken it before, test it at home first. Avoid driving for the first 24 hours until you know how your body reacts.

What’s the safest antihistamine for drivers?

Fexofenadine (Allegra) and levocetirizine (Xyzal) are the safest options. Both are third-generation antihistamines with minimal brain penetration. Clinical trials show no significant driving impairment after single or repeated doses. They’re the preferred choice for people who drive, operate machinery, or need to stay alert.

Do non-drowsy labels mean the drug is safe to drive after?

Not necessarily. Labels like “non-drowsy” are marketing terms, not medical guarantees. Cetirizine (Zyrtec) is labeled non-drowsy, yet studies show it impairs driving in a significant portion of users. Always check the active ingredient. If it’s diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine, or doxylamine, avoid driving. If it’s fexofenadine or levocetirizine, you’re likely safe.

How long should I wait to drive after taking an antihistamine?

For first-generation antihistamines like Benadryl, wait at least 6-8 hours. For second-gen like Zyrtec or Claritin, wait 24 hours if you’ve never taken it before. For third-gen like Allegra or Xyzal, you can usually drive right away-but still test yourself first. The safest approach: take any new antihistamine at night, and wait until the next day to drive.

Can I get pulled over for taking antihistamines?

Yes. While there’s no legal limit for antihistamines like there is for alcohol, police can arrest you for impaired driving if they believe your medication affected your ability to operate a vehicle. If a blood test shows diphenhydramine and you’re in a crash or exhibiting poor driving, you can face DUI charges-even with a 0.00% BAC.

Comments (13)

-

Stuart Rolland October 29, 2025

Okay but let’s be real - I took Benadryl last week because my allergies were screaming and I thought, ‘Eh, I’ll just drive slow.’ Ended up weaving between lanes like I was in a video game. Didn’t crash, but I pulled over and cried a little. My dog in the passenger seat looked at me like I’d betrayed him. I switched to Allegra after that. No more zombie driving. If you’re still using Benadryl for allergies and you drive? You’re not brave. You’re just lucky.

-

Charlos Thompson October 31, 2025

Oh wow. A 12-page essay on why your antihistamine is secretly a drunk driver. Did you also write a 3000-word treatise on why breathing while driving is a liability? Because I need to read that next. Also, ‘third-generation’? Sounds like a new iPhone. Next thing you know, we’ll be paying $400 for a pill that doesn’t make you sleepy - and then the FDA will ban it because ‘some users reported feeling too alert’.

-

Peter Feldges November 1, 2025

While I appreciate the thoroughness of this piece, I must respectfully note that the regulatory disparity between the U.S. and the E.U. is not merely a matter of policy, but of cultural perception toward pharmacological responsibility. In Europe, the state assumes a paternalistic role in protecting citizens from their own choices - a model that, while effective, may not translate directly to a society that prioritizes individual autonomy. That said, the clinical data is unequivocal: first-generation antihistamines impair psychomotor function. The real question is not whether they’re dangerous - but why we continue to normalize their use.

-

Richard Kang November 1, 2025

WAIT WAIT WAIT - so you’re telling me I can’t take Benadryl before my 3-hour drive to the lake?!?!?!?! I’ve been doing this since 2015!! My grandma used it!! My uncle drove a semi with Benadryl in his glovebox!! I don’t feel sleepy!! I feel… focused!! Also, why is Allegra so expensive?? My insurance says ‘no’ and I have a $200 deductible!! This is a conspiracy!! I bet Big Pharma wants me to buy $35 pills so they can buy yachts!!

-

Rohit Nair November 2, 2025

i read this whole thing and i just want to say thank you. i take zyrtec every day and never knew it could affect driving. i thought 'non-drowsy' meant 'no effect at all'. now i know better. i'm switching to allegra next refill. also, i work as a delivery driver in bangalore and this info could save lives here too. maybe someone should translate this into hindi?

-

Wendy Stanford November 3, 2025

It’s not just about the pills. It’s about the illusion of control. We take these tiny white tablets and believe we’ve outsmarted biology - that we can override our own neural architecture with willpower and denial. We are not machines. We are fragile, chemical beings dancing on the edge of biochemical collapse, and yet we strap ourselves into 2-ton metal boxes and call it freedom. The real tragedy isn’t the accident - it’s the quiet, unacknowledged surrender to the myth that we’re still in charge.

-

Jessica Glass November 5, 2025

Oh my god. Someone finally said it. I had a coworker who took Benadryl every morning ‘because it helps me sleep at night’ and then drove 45 minutes to work. I once saw her miss a stop sign, then apologize by saying ‘I didn’t feel sleepy!’ I wanted to scream. You don’t have to feel sleepy to be dangerous. You’re not a hero. You’re a walking liability. Also, why is this even a debate? The science is 50 years old.

-

Krishna Kranthi November 7, 2025

bro i used to take diphenhydramine like candy till my cousin told me he almost crashed because he thought he was fine. now i take allegra and i feel like a new man. also in india most people dont even know what 'second-gen' means. we just grab whatever's cheapest at the pharmacy. maybe we need posters in every kirana store. 'DON'T DRIVE AFTER THIS PILLS' with a picture of a crashed car and a sleepy face. simple. effective.

-

Lilly Dillon November 7, 2025

I switched to Xyzal last year. No drowsiness. No fog. Just clear skies and smooth driving. I didn’t even realize how bad it was until I stopped. Now I feel like I’m driving with all my senses back. Also, I hate when people say ‘I’ve built up a tolerance.’ No, you haven’t. Your brain is just lying to you.

-

Shiv Sivaguru November 8, 2025

why are we even talking about this? just dont drive if you’re on meds. duh. also allegra is overrated. i take cetirizine and i’m fine. stop being dramatic. also why is everyone so scared of a little drowsiness? i nap in the car sometimes. it’s chill.

-

Gavin McMurdo November 9, 2025

Let’s not pretend this is about safety. It’s about liability. The pharmaceutical industry didn’t fund these studies because they care about your life - they care about your lawsuit potential. Third-gen antihistamines are more expensive because they’re patented. The real solution? Regulate the damn labels. Not the drugs. If you want to drive while impaired? Fine. But make the warning bold, red, and in 72-point font. Not tucked under ‘may cause drowsiness’ in Comic Sans. We’re adults. Stop infantilizing us - and start holding manufacturers accountable.

-

Jesse Weinberger November 10, 2025

So… you’re saying Zyrtec is bad? But I read online that it’s ‘non-drowsy’? And I’ve been taking it for years? And I’m fine? So you’re just another ‘science guy’ trying to scare people? I bet you also think the moon landing was fake. Also, I took Benadryl last night and drove to Walmart at 3am. I was fine. I even sang along to ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’. So your ‘science’ is wrong. And also, I don’t trust pharmacists. They’re just salespeople in white coats.

-

Emilie Bronsard November 11, 2025

Thank you for writing this. I’m switching to Allegra tomorrow.