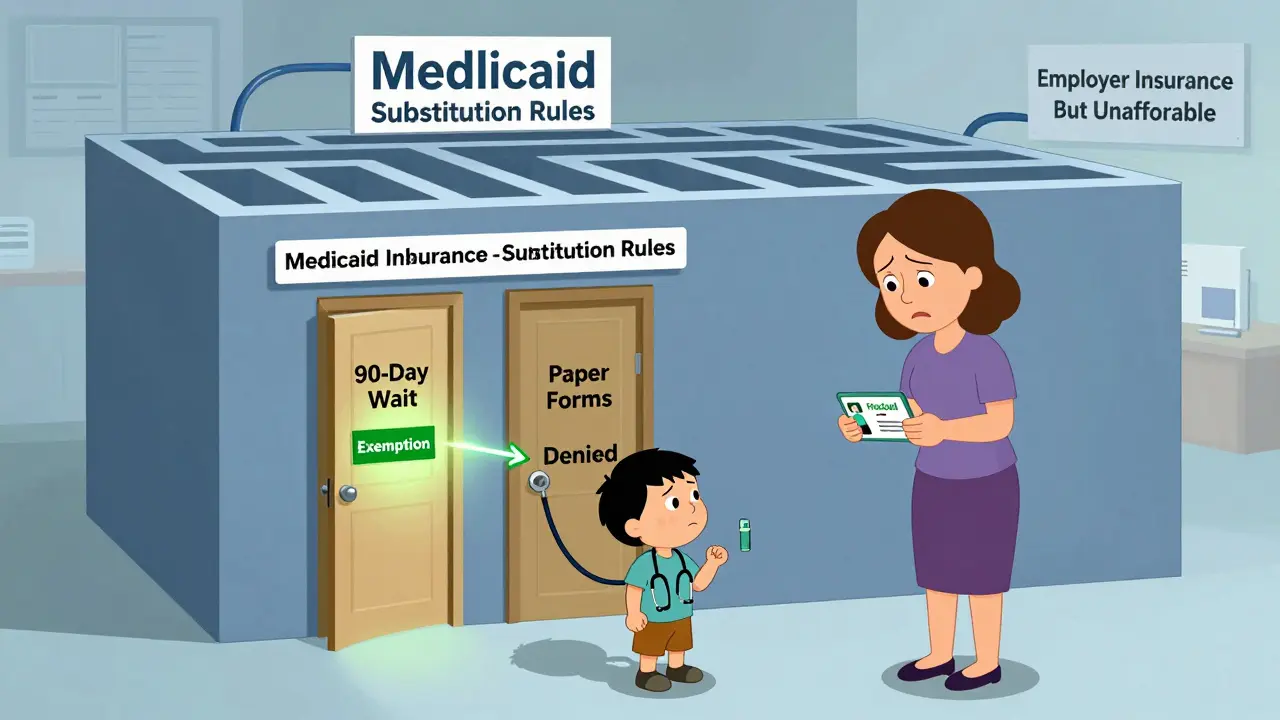

When a family loses their job or switches employers, their kids might suddenly lose private health insurance. In many states, they can quickly switch to Medicaid or CHIP - but not always. Some states force families to wait 90 days before getting public coverage, even if the child is now completely uninsured. Why? Because of Medicaid substitution rules.

What Are Medicaid Substitution Rules?

Medicaid substitution rules exist to stop public programs like Medicaid and CHIP from replacing private health insurance that families could reasonably afford. The idea is simple: if a child has access to employer-sponsored coverage, Medicaid shouldn’t step in as the first option. These rules were written into federal law back in 1997 and got a major update in 2024 under the Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility and Enrollment rule.The goal isn’t to deny kids care - it’s to make sure public money isn’t used when private coverage is already available. But in practice, these rules often create confusion, delays, and coverage gaps. Families lose coverage on Friday, apply for CHIP on Monday, and get denied because of a 90-day waiting period. Meanwhile, the child goes without a doctor’s visit, a prescription, or even an emergency room visit.

The Mandatory Rule: Every State Must Prevent Substitution

All 50 states and Washington, D.C. are required by federal law to prevent Medicaid and CHIP from substituting for private insurance. This isn’t optional. It’s written into 42 CFR 457.805(a) under Section 2102(b)(3)(C) of the Social Security Act. States must have systems in place to check whether a child has access to affordable private coverage through a parent’s job.But here’s where it gets messy: the law doesn’t say how states must do this. That’s why you see wildly different approaches across the country. Some states use automated systems that check private insurance databases in real time. Others still rely on paper forms, phone calls, and mailed documents - processes that can take weeks.

The federal government requires states to allow exemptions to waiting periods in certain cases, like job loss or reduced work hours. But only 15 states go beyond the minimum. In states like Florida, Illinois, and Pennsylvania, families who lose their job can get CHIP coverage immediately. In others, they’re stuck waiting.

The Optional Rule: Waiting Periods and How States Use Them

States can choose to impose a waiting period of up to 90 days before a child can enroll in CHIP if private coverage is available. This is the part that causes the most frustration. Thirty-four states use this waiting period as their main tool to prevent substitution. That means nearly two-thirds of U.S. states make families wait before getting help - even if the child is now uninsured.California, Texas, and New York - the three largest states - all use the 90-day rule. In Texas, CHIP administrators say it prevents parents from dropping employer coverage just to get free public insurance. But a Medicaid worker in Ohio told a Reddit thread: “We get families who lose employer coverage on Friday and need CHIP Monday, but the 90-day rule forces us to deny them for 12 weeks - they often end up uninsured during that time.”

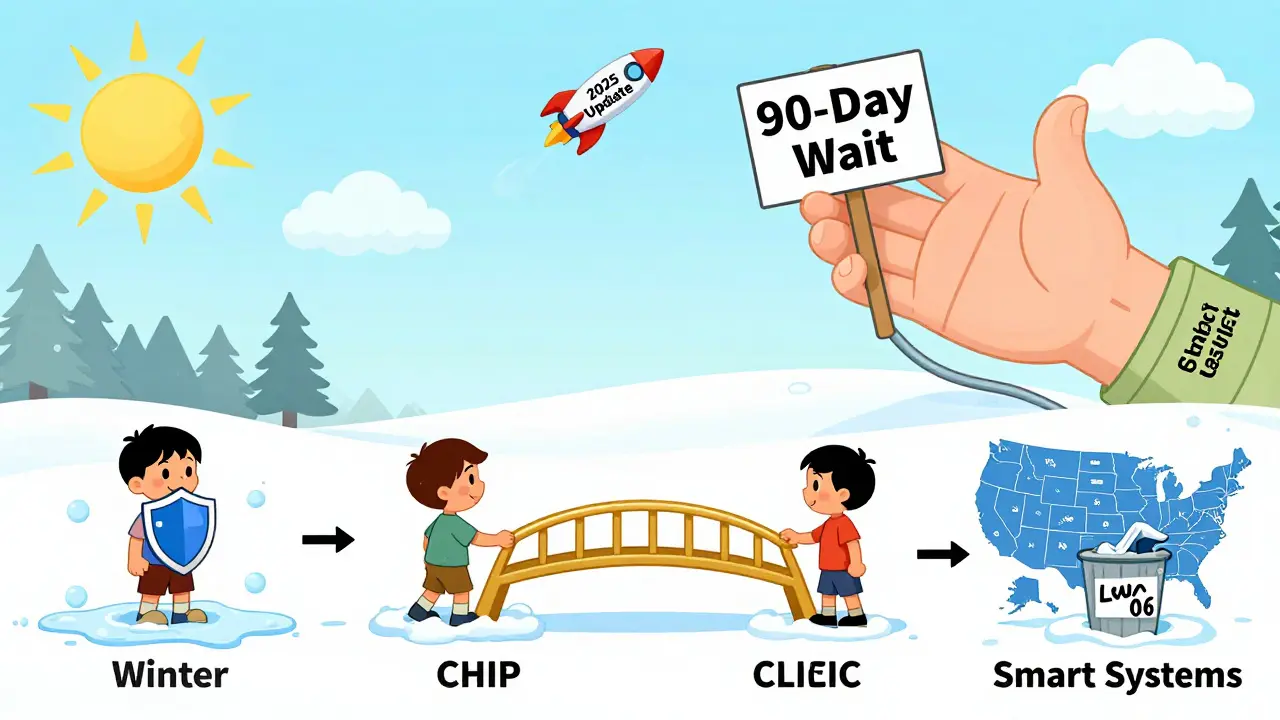

Meanwhile, 16 states don’t use waiting periods at all. Instead, they monitor private insurance through databases or ask families to prove they’ve declined coverage. These states report fewer coverage gaps. A 2023 Urban Institute study found that states with integrated Medicaid-CHIP systems - meaning one application, one eligibility check - had 22% fewer enrollment gaps than states with separate systems.

How States Verify Private Insurance

The biggest challenge for every state? Proving whether private coverage is actually available. The federal government says coverage is “available” if the monthly premium doesn’t exceed 9.12% of household income (based on 2024 IRS guidelines). But verifying that isn’t easy.States have two main tools: database checks and household surveys. Twenty-eight states use real-time data from private insurers through the National Association of Insurance Commissioners’ Health Insurance Resource Database. That means if a parent’s employer offers insurance, the state system can see it instantly.

But 22 states still rely on paper forms or phone interviews. Parents have to provide pay stubs, insurance cards, or employer letters. One state Medicaid director told a 2023 survey that verification takes an average of 14.2 days. That’s two weeks without coverage for a child who might need asthma medication or a dental checkup.

And it gets worse. Some employers offer insurance, but employees decline it because premiums are too high or the network doesn’t include their doctor. Do those families still qualify for CHIP? It depends on the state. In some places, yes. In others, no - even if the coverage is useless to them.

States Doing It Right: Real-Time Data and Automatic Transitions

The best-performing states don’t just check boxes - they fix gaps before they happen. Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Oregon have slashed substitution-related coverage gaps to under 8%, compared to the national average of 21%.Minnesota’s “Bridge Program” is a standout. It connects private insurer databases directly to the state’s Medicaid system. When a parent loses a job, the system automatically flags the child for CHIP enrollment - no paperwork, no waiting. A 2022 Health Affairs case study showed it cut coverage gaps by 63%.

These states also have automatic transitions between Medicaid and CHIP. If a child’s income changes - say, a parent gets a raise - the system switches them from one program to the other without a break in coverage. That’s exactly what the 2024 CMS rule now requires all states to do by October 1, 2025.

The Hidden Cost: Kids Going Uninsured

The biggest failure of substitution rules isn’t the bureaucracy - it’s the kids who fall through the cracks. Even with all the rules in place, 21% of children experience coverage gaps when moving between Medicaid and CHIP, according to CMS’s 2022 evaluation.States with strict substitution rules often see higher rates of complete uninsurance. In Louisiana, after tightening verification rules in 2021, the uninsured rate among low-income children jumped by 4.7 percentage points. That’s nearly 5,000 kids without any coverage for months.

And it’s not just low-income families. Parents in seasonal industries - agriculture, construction, hospitality - lose coverage every year. In states like Arizona and Nevada, where these jobs are common, substitution rules mean kids go without care every winter or summer. The Kaiser Family Foundation found that in these states, children are more likely to become completely uninsured than to get CHIP.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

The March 2024 CMS rule is the biggest update to substitution rules in over a decade. Starting January 1, 2025, every state must report quarterly data on coverage gaps and waiting period use. That transparency will force states to face their own failures.By October 1, 2025, all states must connect their Medicaid and CHIP systems to allow automatic transitions. By December 31, 2025, they must accept eligibility decisions from other programs - like the Affordable Care Act marketplace - without forcing families to reapply.

Industry analysts predict that by 2027, every state will use automated data matching. Manual verification will be a relic. That’s good news. But experts warn: if states don’t also expand exemptions for job loss, reduced hours, or unstable work, the rules will keep hurting the very families they’re meant to protect.

What Families Should Do

If you’re losing private insurance and applying for CHIP:- Ask if your state has a waiting period - and if you qualify for an exemption (job loss, reduced hours, domestic violence).

- Submit proof of lost coverage immediately - termination letter, pay stub showing reduced hours, or employer confirmation.

- Don’t wait for approval. If your child needs care now, go to a community health center. They can’t turn you away.

- Call your state’s Medicaid office and ask for the substitution rule policy. Get it in writing.

Some states have advocacy groups that help families navigate these rules. Families USA and local child health coalitions offer free assistance. Don’t assume you’re stuck - know your rights.

Why This Matters Beyond the Numbers

Medicaid substitution rules were designed in the 1990s, when most people got insurance through stable, full-time jobs. Today, gig work, variable hours, and short-term plans are the norm. The rules haven’t kept up.They punish families for working - for taking a job with benefits, even if the premiums are too high. They create paperwork nightmares for caseworkers who just want to help. And they leave kids without care while bureaucrats wait for a fax.

The real solution isn’t more rules. It’s smarter systems. Real-time data. Automatic enrollment. Fewer barriers. The states that are getting it right prove it’s possible. The question is: will the rest catch up before another child goes without care?

Are Medicaid substitution rules the same in every state?

No. While all states must prevent Medicaid and CHIP from replacing private insurance, how they do it varies. Thirty-four states use a 90-day waiting period; 16 don’t. Some use automated database checks, others rely on paper forms. Exemptions for job loss or reduced hours are optional, and only 15 states offer more than the federal minimum.

Can a child be denied CHIP if a parent has job-based insurance?

Yes - but only if that insurance is considered affordable (premiums under 9.12% of household income) and accessible. If the employer offers coverage but the parent can’t afford it, or if the network doesn’t cover their doctor, the child may still qualify for CHIP. States vary in how strictly they enforce this, so families should always apply and ask about exemptions.

What happens if a family misses the 90-day waiting period?

If a state uses a waiting period and the family doesn’t qualify for an exemption, they must wait the full 90 days before enrolling in CHIP. During that time, the child may be uninsured. Families can seek emergency care at community health centers or hospitals, which are legally required to treat children regardless of insurance status. Some states offer temporary assistance programs during this gap.

How do I know if my state has a substitution waiting period?

Check your state’s Medicaid or CHIP website. Look for terms like “substitution prevention,” “private insurance verification,” or “waiting period.” You can also call the state’s Medicaid helpline and ask: “Do you require a waiting period for CHIP if a child has access to employer-sponsored insurance?” Request written policy documents if possible.

Are there any exceptions to the 90-day waiting period?

Yes. Federal rules require states to allow exemptions for job loss, reduced work hours, divorce, domestic violence, or loss of employer coverage. Fifteen states go further, adding exemptions for seasonal workers, military deployment, or homelessness. Always ask if you qualify - many families don’t know these exceptions exist.

Comments (14)

-

roger dalomba December 24, 2025

So let me get this straight - we’ve got a system designed in 1997 to handle 9-to-5 jobs, and now we’re using it to manage gig workers, part-timers, and parents who work two jobs just to keep the lights on? Brilliant. Just brilliant. 🙃

-

Brittany Fuhs December 25, 2025

It's not that complicated. If you have access to employer-sponsored insurance, you should use it. Medicaid isn't a backup plan for people who can't be bothered to pay for their own coverage. This isn't socialism - it's fiscal responsibility.

-

Sandeep Jain December 26, 2025

I work in a hospital in Delhi, and we see kids from the US come in with no insurance after waiting 90 days. One boy had pneumonia because his mom lost her job and couldn't get CHIP fast enough. It breaks my heart. This isn't policy - it's cruelty wrapped in bureaucracy.

-

Erwin Asilom December 28, 2025

If your state still uses paper forms for insurance verification, you're operating in the Stone Age. Real-time data integration isn't a luxury - it's a moral imperative. The technology exists. The will doesn't.

-

Nikki Brown December 28, 2025

Ugh. Another one of these posts where people act like kids are somehow entitled to free healthcare. If you can't afford insurance, maybe don't have kids? Just saying. 😔

-

Peter sullen December 29, 2025

It is imperative to acknowledge, in a rigorously structured and evidence-based manner, that the structural inefficiencies inherent in the current Medicaid substitution paradigm are not merely administrative inconveniences - they are systemic failures in child health equity infrastructure. The 90-day waiting period constitutes a non-trivial impediment to continuity of care, and its persistence reflects a profound misalignment between policy design and population-level health outcomes.

-

Becky Baker December 30, 2025

Why should American taxpayers fund kids whose parents could’ve just stayed at their job? If you quit or get fired, tough luck. That’s the American dream - work or go without.

-

Rajni Jain December 31, 2025

My cousin lost her job last year and waited 3 months for CHIP. Her son missed his asthma meds. He ended up in the ER. They finally approved it - but only after he got sick. This system is broken. Not everyone can afford to be a hero.

-

Natasha Sandra January 2, 2026

Y’all need to stop being so harsh 😔 Kids are innocent! If a parent loses their job, the kid shouldn’t pay for it. 🤍 We can do better - we’re America, not a spreadsheet.

-

Sumler Luu January 3, 2026

Some states have it right. Others are just dragging their feet. The solution isn’t to eliminate the rules - it’s to fix the implementation. Real-time data, automatic transitions, clear exemptions. Done.

-

sakshi nagpal January 4, 2026

It's fascinating how policy evolves with labor markets. The 1997 framework assumed stable employment. Today, we have hybrid work, freelance gigs, and seasonal industries. The rules need to reflect reality - not nostalgia.

-

Sophia Daniels January 5, 2026

Let me get this straight - we’re letting kids go without insulin because a bureaucrat in Texas is waiting for a fax? This isn’t policy. This is a horror movie written by a DMV employee. 🤡

-

Steven Destiny January 6, 2026

Stop making excuses. The technology to fix this exists. The will exists in some states. If you’re not doing it, you’re choosing to let kids suffer. That’s not policy - that’s malice with a title.

-

Fabio Raphael January 8, 2026

What’s the actual cost of denying a child care for 90 days? ER visits? Long-term health damage? Lost parental productivity? The savings from avoiding CHIP enrollment are dwarfed by the downstream costs. We’re just moving the expense around - and the kids pay the price.