Immune System Risk Assessment for Fungal Skin Discoloration

Your Personal Risk Assessment

This tool helps you understand your risk of developing fungal skin discoloration based on your health factors and immune system status. It's not a diagnostic tool but provides insight into potential risk factors that may require medical attention.

Recommended Actions

Continue maintaining good skin hygiene and healthy lifestyle habits. Keep skin dry and clean, especially in moisture-prone areas. Monitor for any new discoloration and consult a dermatologist if you notice persistent changes.

Key Takeaways

- Fungal skin discoloration occurs when dermatophytes or yeast invade skin layers, altering pigment.

- The immune system’s T‑cells and inflammatory pathways decide whether the infection stays mild or spreads.

- People with weakened immunity-due to diabetes, HIV, or medications-are most at risk.

- Early diagnosis relies on visual clues, a skin‑scrape test, and sometimes a culture.

- Topical or oral antifungals, plus measures to boost immune health, usually restore normal color within weeks.

When patches of skin suddenly turn lighter or darker, many assume it’s just a harmless bruise or sunspot. In reality, an unseen fungal invader could be the culprit, and the way your body’s immune system reacts often dictates how the discoloration looks and how long it lasts.

Fungal skin discoloration is a change in skin colour caused by fungal organisms that break down melanin or trigger inflammation that alters pigment production. Common culprits include dermatophytes (the ring‑worm family), Candida species, and less‑common molds. While the discoloration itself is a cosmetic concern, it often signals an underlying immune response that deserves attention.

Below, we’ll walk through what causes these pigment shifts, why the immune system matters, how doctors figure out what’s happening, and what you can do to clear things up.

What Triggers Fungal Skin Discoloration?

Fungi thrive in warm, moist environments, so the skin’s folds, feet, and groin are prime real estate. When a fungus lands on the skin, three main mechanisms can change colour:

- Melanin degradation: Certain dermatophytes produce enzymes that break down melanin, the pigment that gives skin its hue. As melanin is destroyed, the affected area appears lighter (hypopigmentation).

- Inflammatory hyperpigmentation: The immune system’s fight‑fire releases cytokines that stimulate melanocytes, leading to darker patches (hyperpigmentation) after the infection clears.

- Secondary bacterial infection: A fungal breach can invite bacteria, causing redness that later turns brown or gray as healing progresses.

For example, Tinea versicolor-caused by the yeast Malassezia-often produces small, lighter‑than‑surrounding spots on the trunk. The yeast consumes lipids on the skin and releases acids that temporarily suppress melanin production.

How the Immune System Shapes the Outcome

Fungi are opportunistic; they exploit a gap in your defenses. The immune system reacts in two key ways:

- Innate immunity: Skin barrier proteins (like filaggrin) and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) act as the first line of defense. A genetic deficiency in filaggrin can let fungi penetrate deeper, increasing discoloration risk.

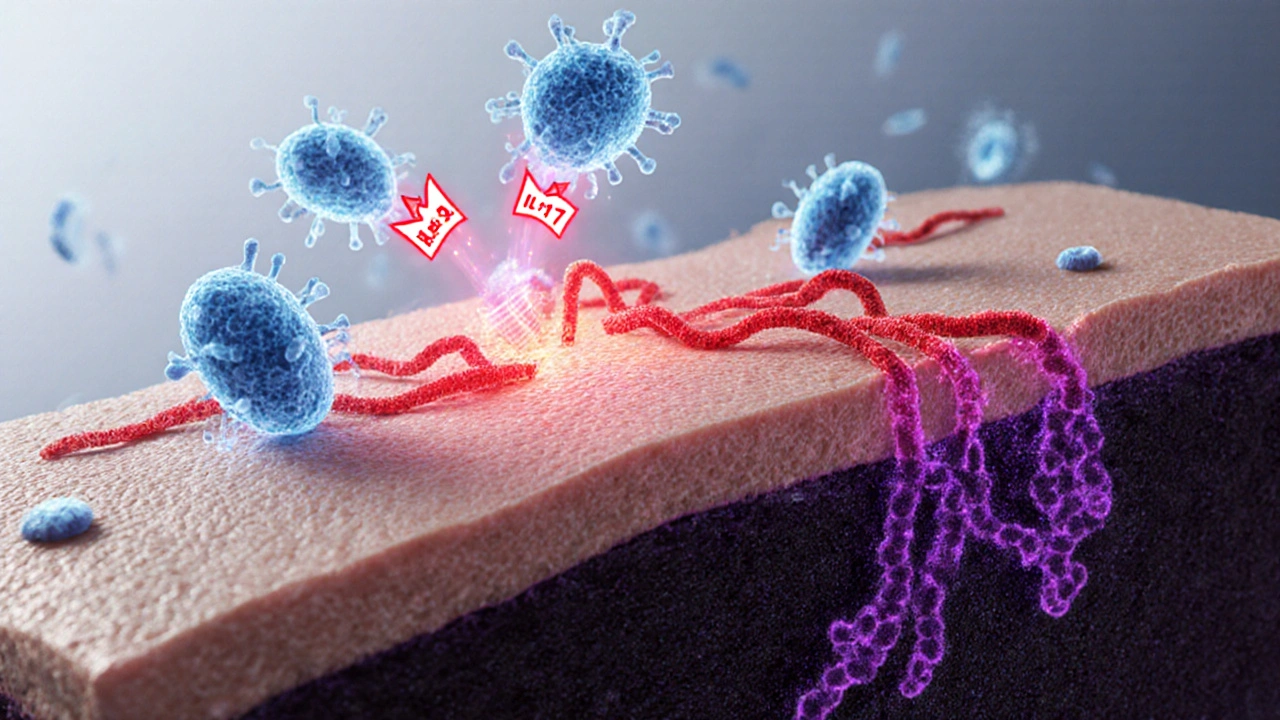

- Adaptive immunity: T‑cells, especially Th17 subsets, release interleukin‑17 (IL‑17) to recruit neutrophils to the infection site. When this response is too weak-common in patients on corticosteroids or biologics-the fungus spreads, causing larger, more irregular colour changes.

When the immune response overshoots, the inflammation itself triggers melanocyte hyperactivity, resulting in darkened patches that linger even after the fungus is gone.

Who Is Most at Risk?

Anyone can get a fungal skin infection, but certain conditions tilt the odds:

| Risk Factor | How It Affects Immunity | Typical Discoloration Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus | Reduced neutrophil chemotaxis; higher glucose feeds fungi | Diffuse hyperpigmented macules on feet and groin |

| HIV/AIDS | Low CD4+ T‑cell count impairs Th17 response | Extensive hypopigmented plaques, often on trunk |

| Topical steroid overuse | Suppresses local cytokine production | Mixed light‑dark patches where steroids were applied |

| Obesity | Skin folds retain moisture; adipose tissue releases inflammatory mediators | Intertriginous areas (under breasts, abdomen) with irregular coloration |

| Genetic filaggrin mutation | Compromised barrier allows deeper fungal invasion | Linear hypopigmented streaks on arms or legs |

Diagnosing the Condition

A visual exam often raises suspicion, but confirming a fungal cause requires a few quick steps:

- Skin scraping: A sterile blade collects surface scales. Under a microscope, you’ll see hyphae (branching filaments) or yeast spores.

- Wood’s lamp examination: Certain species fluoresce bright yellow‑green under ultraviolet light, helping differentiate Malassezia infections.

- Culture: While not always necessary, growing the organism on Sabouraud agar provides species‑level identification, useful for resistant cases.

- Blood work (optional): In immunocompromised patients, a CBC with differential and CD4 count can gauge immune status.

All these tests are quick, cheap, and usually done in a primary‑care or dermatology office.

Treatment Strategies

Effective therapy tackles two fronts: eradicate the fungus and modulate the immune response to prevent recurrence.

Topical Antifungals

For localized spots, creams or sprays containing clotrimazole, miconazole, or terbinafine are first‑line. Apply twice daily for 2‑4 weeks. The active ingredient disrupts the fungal cell membrane by binding ergosterol, leading to cell death.

Oral Antifungals

If the infection covers a large area, recurs, or involves the nail matrix, doctors may prescribe oral agents like itraconazole or fluconazole. Dosing varies: for tinea versicolor, a single 400mg dose can be enough; for chronic dermatophytosis, a 12‑week regimen is common.

Immune Support

Alongside medication, strengthening the immune system speeds recovery:

- Nutrition: Adequate zinc (15mg/day) and vitaminD (800-1000IU) enhance T‑cell function.

- Sleep: 7-8hours nightly improves cytokine balance.

- Stress reduction: Chronic cortisol suppresses Th17, so mindfulness or moderate exercise helps.

Preventing Recurrence

After clearing the infection, keep the skin dry and breathable. Switch to cotton socks, avoid tight shoes, and use antifungal powders in high‑friction zones. For people on long‑term immunosuppressants, a dermatologist may recommend a prophylactic topical applied once weekly.

When to Seek Professional Help

If you notice any of the following, book an appointment promptly:

- Rapid spreading of colour changes over more than 5cm

- Accompanying itching, burning, or pain

- Signs of systemic infection-fever, chills, malaise

- Underlying conditions like HIV, uncontrolled diabetes, or recent chemotherapy

Early intervention limits skin damage and reduces the chance of permanent pigment loss.

Real‑World Example

Maria, a 42‑year‑old accountant from Houston, developed light‑colored patches on her back after a summer camping trip. She’s diabetic and uses a corticosteroid cream for eczema. A quick skin‑scrape revealed Malassezia spores, and a Wood’s lamp showed bright fluorescence. Her doctor prescribed a 2‑week course of topical terbinafine and recommended tighter glucose control, a zinc supplement, and switching to a fragrance‑free moisturizer. Within three weeks, the patches faded and her skin tone evened out.

Key Takeaway Summary

Fungal skin discoloration isn’t just skin‑deep; it’s a clear sign of how your immune system is handling a hidden invader. By spotting the colour changes early, getting a simple lab test, and treating both the fungus and any immune gaps, you can restore healthy skin and avoid lingering marks.

fungal skin discoloration often signals an underlying immune challenge-address it promptly for the best outcome.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can fungal skin infections cause permanent pigmentation loss?

If treated early, most discoloration resolves within weeks. However, prolonged infection or aggressive inflammation can damage melanocytes, leading to lasting hypopigmentation. Early antifungal therapy and skin‑care measures reduce this risk.

Is a Wood’s lamp exam necessary for diagnosis?

It’s not required but helpful. Certain yeasts, especially Malassezia, fluoresce distinct colors under UV light, helping clinicians confirm a fungal cause without waiting for culture results.

How do immunosuppressive drugs affect fungal skin discoloration?

Drugs like prednisone or TNF‑α inhibitors blunt the Th17 response, making the skin more vulnerable to fungal invasion. Patients on these medications should monitor skin changes closely and may need prophylactic topical antifungals.

Are there natural remedies that help clear fungal discoloration?

Tea tree oil (5‑10% concentration) and apple cider vinegar rinses have modest antifungal activity, but they’re not replacements for prescription meds in moderate to severe cases. Use them as adjuncts after consulting a clinician.

What lifestyle changes lower my risk of fungal skin discoloration?

Keep skin dry, wear breathable fabrics, manage blood‑sugar levels if diabetic, avoid prolonged antibiotic or steroid courses, and practice good foot hygiene-dry between toes, change socks daily, and use antifungal powder in sweaty shoes.

Comments (14)

-

Ashley Helton October 12, 2025

Oh great, another quiz that tells you what you already kind of knew about your skin.

-

Alex Mitchell October 15, 2025

Honestly, if you’re diabetic, your skin’s sugar levels can invite those pesky fungi – keep your glucose in check and you’ll lower the odds. Also, a bit of proper foot care goes a long way; dry those areas and don’t ignore any weird coloration. :)

-

Amanda Jennings October 18, 2025

Hey folks! If you notice any persistent itching or patches, don’t wait – grab a dermatologist appointment ASAP. Early detection means easier treatment and less chance of spreading. Stay motivated, your skin will thank you!

-

alex cristobal roque October 20, 2025

Just to add on Alex’s point, immunosuppressant meds can really tilt the balance in favor of fungal overgrowth. Those drugs dampen the immune surveillance that usually keeps opportunistic organisms in check, so regular skin checks become even more crucial. A simple antifungal regimen can prevent a full‑blown infection later.

-

Bridget Dunning October 23, 2025

From a dermatogenetics perspective, filaggrin loss‑of‑function mutations compromise the skin barrier integrity, predisposing individuals to xerosis and secondary fungal colonisation. Therefore, adjunctive emollient therapy is advisable for carriers of such genotypes.

-

Shweta Dandekar October 26, 2025

It is absolutely imperative!! One must maintain meticulous skin hygiene; daily cleansing, thorough drying, and immediate attention to any macerated areas are non‑negotiable. Neglecting these basic steps, especially in immunocompromised hosts, invites not just fungal discoloration but a cascade of secondary infections!!!

-

Dominic Dale October 28, 2025

The so‑called "risk calculator" is just a smokescreen for the pharma lobby; they want you to think you need an expensive prescription antifungal for a harmless skin patch. In reality, most of these discolorations are the result of environmental spores that our bodies have been dealing with since the dawn of time. The government agencies that approve these tools are funded by the same companies that sell the creams. They track your clicks, your data, and then push targeted ads for products you never asked for. Meanwhile, they ignore the real culprits: chronic stress, poor sleep, and a diet high in refined sugars that sabotage immunity. If you look at epidemiological data, regions with low pharmaceutical penetration have comparable, if not lower, rates of fungal skin issues. This suggests lifestyle factors trump any synthetic medication. The rise in “immune‑related” checklists is a deliberate attempt to medicalize everyday variations in skin tone. By labeling normal pigmentation changes as pathological, they create a market for unnecessary treatments. The algorithm scores you based on arbitrary checkboxes, not on any rigorous clinical trial outcomes. Moreover, the tool fails to mention that over‑the‑counter remedies exist that are both effective and inexpensive. Did you know that simple hygiene measures and probiotic supplementation can restore a healthy skin microbiome? The hidden agenda is to keep you dependent on a cycle of quarterly dermatologist visits and pricey prescription refills. In short, don’t be fooled by a shiny UI – trust your own observations and common sense over a corporate‑backed questionnaire.

-

christopher werner October 31, 2025

I see where Dominic’s coming from, but it’s probably best to just keep an eye on any changes and talk to a doctor if they linger.

-

Danielle Watson November 3, 2025

Totally agree with keeping skin dry especially after workouts. Simple steps make a big difference.

-

Kimberly :) November 5, 2025

Love the info! 😊 Just a reminder that a balanced diet and staying hydrated can boost skin health too. 🌱

-

Sebastian Miles November 8, 2025

FYI, corticosteroid tapers can increase fungal risk-monitor closely.

-

Hoyt Dawes November 11, 2025

Wow, another “must‑read” post about skin stuff. Yawn.

-

Jeff Ceo November 13, 2025

Enough with the fluff – if you have the symptoms, get a proper diagnosis now.

-

Jean-Sébastien Dufresne November 16, 2025

In my country we rely on traditional remedies; modern risk tools are just another form of cultural imperialism!!! :)